Successful laparoscopic treatment of iatrogenic distal esophageal perforation during sleeve gastrectomy

Introduction

Bariatric surgery has been recognized as the most effective long-term treatment for severe obesity. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is one of the most common operation performed for morbid obesity worldwide (1,2). The operation consists in the creation of a 100–150 mL gastric tube along the greater gastric curvature with fundectomy and antrum preservation (3). It has been shown that LSG is a safe and effective procedure with durable weight loss and comorbid resolution in the long-term follow-up (4). In order to ensure a consistent and reproducible sleeve size, the international SG Expert Panel Consensus Statement stated that the gastric tube should be fashioned over an orogastric bougie (3).

Complication of LSG include hemorrhage (1–6%), gastric leak (1–5%), and intra-abdominal abscess (1%) (5). Iatrogenic distal esophageal perforation is a rare but potential complication of the blind bougie advancement (6). The early diagnosis is challenging and the timely treatment is mandatory. However, no clear consensus exist on the preferred management of such complication and few case reports are described in the literature.

We report the case of a 61-year-old female that experienced iatrogenic distal esophageal perforation during sleeve gastrectomy successfully treated with laparoscopic suturing.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old obese female with hypertension requiring medication was admitted to our hospital after previous unsuccessful dietary regimen. Her body mass index (BMI) was 41.2 kg/m2 (weight: 99 kg; height: 178 cm) and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score was 2.

The patients underwent LSG. The overall operation time was 60 minutes and the intraoperative blood loss was negligible. During the operation, the placement of the orogastric bougie (36Fr) was laborious. Because the suspicion of iatrogenic perforation an intraoperative endoscopy was performed with no evidence of full thickness injury or air leak. The dye blue methylene test performed through the nasogastric tube was negative. A silicone drain was placed along the gastric suture line.

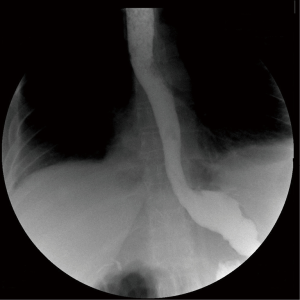

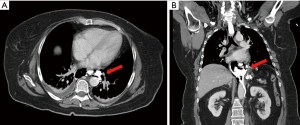

Six hours after the operation, the patient complained of an acute lower back pain and worsening dyspnea without fever. The abdominal drain was silent and the complete blood count was negative. A thoraco-abdominal CT scan with water-soluble agent (gastrografin) showed a full-thickness postero-lateral perforation of the distal esophagus with mediastinal contamination (Figure 1). For this reason, the patient was transferred urgently to the operative theatre.

Pneumoperitoneum was induced with the Veress needle placed in the left subcostal area (Palmer point). The surgical ports were placed in the same positions of the LSG. The left lobe of the liver was retracted and the dissection was started to access the cardia. The diaphragmatic crura was identified, the posterior mediastinum was dissected free showing mediastinal collection with free air. The esophagus was encircled, suspended, and retracted caudally with a Penrose drain to achieve a complete circumferential visualization of the distal esophageal wall. A 15 mm full thickness perforation of the left posterior aspect was detected with vital and everted margins. The perforation was sutured with four absorbable interrupted stitches (2.0 Vicryl®) every 4–5 mm starting from the superior and inferior edge. An intraoperative endoscopy was performed to rule out residual leak; the air leak test was negative (Figure 2). A mediastinal silicone drain was left and postoperative broad-spectrum antibiotics treatment was adopted with carbapenems. The hospital course was uneventful and a gastrografin swallow study performed on 4th postoperative day was negative for extravasation (Figure 3). The patient was allowed to eat a semiliquid diet and the drain was removed on 6th postoperative day. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 10th. The 6-month follow-up was uneventful with regular weight loss.

Discussion

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is an effective surgical option for the management of morbid obesity. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) reported that in the United States, 135,409 LSGs were performed in 2017, which accounted for 59% of all bariatric procedures. That number increased by 52% from 2014 and 18% from 2011 (8).

Complication after LSG include hemorrhage (1–6%), staple-line gastric leak (1–5%), and intra-abdominal abscess (up to 1%) (5). Iatrogenic esophageal perforation related to bougie advancement is a rare but potential life threating complication of bougie insertion (6). The flexibility of the bougie tip and the anatomic variation of the His angle are potential risk factors for esophageal perforation (9,10). The distension of the gastric fundus due to intubation maneuvers may reduce the acute His angle determining an unintended curvature of the gastroesophageal junction. In addition, the presence of chronic gastroesophageal reflux may cause rigidity of the cardia because of submucosal fibrosis. For these reasons the advancement of the calibration probe should be done cautiously and the difficult ab-oral progression or re-positioning of the bougie should raise the suspicion of iatrogenic perforation.

In general, esophageal perforation is associated with a variable clinical presentation and pose a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge (11,12). Causes of perforation are extremely heterogeneous with more than 50% caused by iatrogenic injury during upper endoscopy (13). The prompt diagnosis, stabilization of the patient, and assessment for operative or nonoperative management are major principles in the treatment of such life-threatening injuries. The diagnostic delay, the etiology of the perforation, the type of repair, the location of perforation, and patient comorbidities may affect morbidity and mortality (13-18). A delayed treatment (more than 24 hours from symptoms onset) has been demonstrated to be associated with a doubling mortality rate because of extra luminal spillage and inflammation (16). The etiology may affect mortality with higher death rate for spontaneous (39%), iatrogenic (19%), and traumatic perforation (9%) (11). Cervical perforation is associated with lower mortality rates (6%), compared to thoracic (34%) and abdominal perforation (29%) (14).

Treatment approaches are extremely heterogeneous and the management is often left to physician’s preference. Non-operative management, endoscopic treatment or surgical operation are feasible options and the decision should be tailored on each patient (19-21). Esophageal stents could be considered in hemodynamically stable patients with subcentimetric esophageal perforation to restore visceral integrity and prevent further spillage (22). Endoscopic clipping and vacuum therapy have been described in selected patients but their role in the management algorithm should be better defined (20). Surgical primary closure with or without tissue reinforcement is a feasible option in case of recent perforation with limited contamination. Closure of perforation could be performed with absorbable interrupted sutures in single or double layer (23). The integrity of the repair can be reinforced with the use of a vascularized pedicle flap or, in case of distal esophageal injury, the suture can be buttressed with an anterior or posterior fundoplication (24). Minimally invasive thoracoscopic or laparoscopic esophageal suturing is feasible in selected cases with iatrogenic esophageal perforation, minimal perivisceral contamination and vital edges (25).

Endoscopy should be always performed in case of difficult bougie positioning and suspicion of perforation. As in our case, a false negative endoscopic examination may occur because the dense fibroareolar tissue of the posterior mediastinum could mask the perforation. For this reason, we believe that in case of suspicion, an adequate opening of the posterior mediastinum and caudal esophageal retraction are mandatory in order to obtain a circumferential rendez-vous laparoendoscopic inspection of the distal esophagus. Laparoscopic suturing could be endoscopically guided to check for the completeness of the repair. In the present case, the fashioning of a posterior fundoplication was not feasible because of the previous fundectomy during sleeve gastrectomy.

Conclusions

The advancement of orogastric bougie for the sleeve gastrectomy calibration should be done prudently. In case of difficult placement, there should be a suspicion for esophageal injury. The opening the posterior mediastinum and distal mobilization of the esophagus are mandatory to achieve adequate visualization of the perforation. The timely minimally invasive suturing may allow successful repair and esophageal salvage in patients with limited contamination.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ls.2018.11.04). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ponce J, DeMaria EJ, Nguyen NT, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of bariatric surgery procedures in 2015 and surgeon workforce in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016;12:1637-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 2013;23:427-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal RJ, Diaz AA, Arvidsson D, et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:8-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gadiot RP, Biter LU, van Mil S, et al. Long-Term Results of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy for Morbid Obesity: 5 to 8-Year Results. Obes Surg 2017;27:59-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Debs T, Petrucciani N, Kassir R, et al. Complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: can we approach a 0% rate using the largest staple height with reinforcement all along the staple line? Short-term results and technical considerations. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Theodorou D, Doulami G, Larentzakis A, et al. Bougie insertion: A common practice with underestimated dangers. Int J Surg Case Rep 2012;3:74-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua E, Aiolfi A, Tornese S, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of the distal iatrogenic esophageal perforation with interrupted sutures. An intraoperative endoscopy was performed to guide the laparoscopic suturing and to check for the completeness of the repair. Asvide 2018;5:870. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/28507

- Available online: https://asmbs.org/

- Gagner M, Huang RY. Comparison between orogastric tube/bougie and a suction calibration system for effects on operative duration, staple-line corkscrewing, and esophageal perforation during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 2016;30:1648-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu-Gazala S, Donchin Y, Keidar A. Nasogastric tube, temperature probe, and bougie stapling during bariatric surgery: a multicenter survey. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:595-600; discussion 600-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aiolfi A, Inaba K, Recinos G, et al. Non-iatrogenic esophageal injury: a retrospective analysis from the National Trauma Data Bank. World J Emerg Surg 2017;12:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaman L, Iqbal J, Kundil B, et al. Management of Esophageal Perforation in Adults. Gastroenterology Res 2010;3:235-44. [PubMed]

- Biancari F, Saarnio J, Mennander A, et al. Outcome of patients with esophageal perforations: a multicenter study. World J Surg 2014;38:902-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones WG 2nd, Ginsberg RJ. Esophageal perforation: a continuing challenge. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;53:534-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Port JL, Kent MS, Korst RJ, et al. Thoracic esophageal perforations: a decade of experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1071-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, et al. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77:1475-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biffl WL, Moore EE, Feliciano DV, et al. Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Diagnosis and management of esophageal injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:1089-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali JT, Rice RD, David EA, et al. Perforated esophageal intervention focus (PERF) study: a multi-center examination of contemporary treatment. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhatia P, Fortin D, Inculet RI, et al. Current concepts in the management of esophageal perforations: a twenty-seven year Canadian experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:209-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bona D, Aiolfi A, Rausa E, et al. Management of Boerhaave's syndrome with an over-the-scope clip. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:752-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leers JM, Vivaldi C, Schäfer H, et al. Endoscopic therapy for esophageal perforation or anastomotic leak with a self-expandable metallic stent. Surg Endosc 2009;23:2258-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dasari BV, Neely D, Kennedy A, et al. The role of esophageal stents in the management of esophageal anastomotic leaks and benign esophageal perforations. Ann Surg 2014;259:852-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sabanathan S, Eng J, Richardson J. Surgical management of intrathoracic oesophageal rupture. Br J Surg 1994;81:863-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richardson JD. Management of esophageal perforations: the value of aggressive surgical treatment. Am J Surg 2005;190:161-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonavina L, Aiolfi A, Siboni S, et al. Thoracoscopic removal of dental prosthesis impacted in the upper thoracic esophagus. World J Emerg Surg 2014;9:5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Bevilacqua E, Aiolfi A, Tornese S, Tringali D, Panizzo V, Micheletto G, Bona D. Successful laparoscopic treatment of iatrogenic distal esophageal perforation during sleeve gastrectomy. Laparosc Surg 2018;2:65.